Each exhibition aims to develop a new strand of interest in the environment and to stimulate related activity and events, timely in an era when we need to be increasingly wary of all kinds of threats from pollution, species loss, deforestation and climate change.

There is no finishing line, however, there are many ways we might know when certain aims have been achieved. Above all, we look for a change – change in thinking and interpretation of the environment, improvement in understanding, recognition of its beauty, seeing its detail, being alert to its fragility, its dangers. We look for new engagement and renewed interest in the environment, stimulated by art. We find new connections between people from different disciplines, able to speak in new ways to each other as a result of the stimulus provided by art. The study and creation of art is never predictable and therefore it is all the more likely that results will be unexpected, surprising, unusual.

Definitions

Thinking about the environment includes noticing the detail of our surroundings and caring for what is in need of our attention, looking out for signs of stress, over-exposure, pollution. We take a very broad view about how we define the environment as that leaves most opportunity for getting involved, both artistically and in terms of activism and political engagement. The environment covers everything from the air we breathe, the ground we walk on, the spaces we live in, the surroundings which frame our lives, localities, lands and seas.

One of the most captivating definitions of the environment was written in 1971 for The Environmental Handbook:

‘Listen friend’, he answered, ‘You are the environment, or part of it, and you are certainly a product of it, just as I am.‘ ‘The environment is the room, the flat, the house where you live: the factory, the office, the shop where you work; your road, your parish, your village, town or city: Britain, Europe, the world – even the space the world sails through. It’s the street where your children play, the park they take the dog in, the flowers, the trees, the animals and birds, the fields, the crops, the streams, the waterfalls. It’s the fish, the cliffs, the seashore, the sea itself, the hills and the mountains, the pubs, the bingo halls, the lanes, the motorways, the highways and byways, the farms, the rows of shops and houses, the dustbins, the historical buildings, the trains and buses and cars. It’s the music and dancing and peaches and cream. It’s the insects, an empty tin can, aeroplanes, pictures, pollen and the leaves that fall from the trees. It’s the smoke from a fire, a wormcast on the lawn, a cigarette end in the gutter, books, papers, greenfly on the roses, the paint on your front door, unbreakable plastic, the rain on the roof, an empty beer bottle, the heather and the bracken and the butterflies. It\s the air you breathe, the blue sky, peace and quiet, the clouds and the sun.’

Barclay Inglis, 1971, The Environmental Handbook (ed John Barr), p. 217.

GroundWork Gallery – every exhibition is a call to action

Making the connection between environmental awareness and contemporary art of the highest quality is what GroundWork gallery is all about. More than that, the gallery shows (and sells) art which can stimulate greater understanding of the environment and lead to campaigning for its sustainability. Every exhibition becomes a call to action. The gallery is in central King’s Lynn, in a former carpenter’s workshop, opposite the famous grade 1 listed Custom House of 1683. It sits directly on the River Purfleet, within sight of the Great Ouse, the town’s historic trading river, which linked it culturally and economically to the Baltic states of the medieval Hanseatic League. The rivers are largely quiet now, but for the silent threats of climate change. The whole town sits in a flood plain. Hence the imperative to consider the consequences, which the gallery does assiduously through art, showing work that helps us to think about the threats, but in the most positive ways. The artists set the tone and produce the big stories, but the public viewing and responding to art is just as important. Properly encouraged, this can entail a series of valuable conversations and cultural responses which can initiate unexpected insights and revelations and sometimes, solutions to problems.

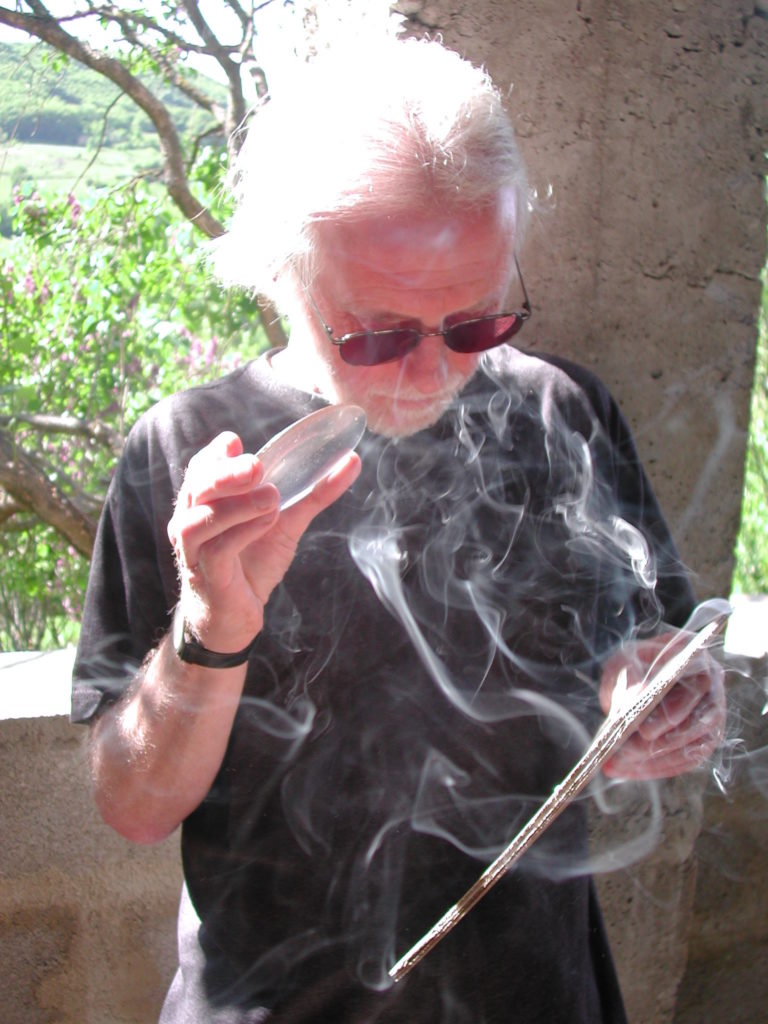

The gallery opened in Summer 2016 with Sunlight and Gravity, containing exquisite works by the late Roger Ackling, made by burning sunlight marks onto driftwood. Shortly before he died of motor neurone disease, the artist agreed to exhibit, bringing in his best friend, Richard Long to show alongside him. At his suggestion, Richard made a new large mud drawing for the gallery wall, by throwing at it a bucket of dilute mud from the tidal Great Ouse. As the mud dried, it gradually revealed its structural pattern, looped high on the wall and beautifully feathered and branched. It remains as a signature work, as a symbol of the will of nature and the knowledge of the artist recognising its power. If it wasn’t already evident, what has also become even clearer through the ten exhibitions that have succeeded Sunlight and Gravity, is how significant a figure is Richard Long. While he never professes to be ‘an environmental artist’ his work, often conducted alone, outside, in challenging locations around the world, has given inspiration – and courage – to so many young artists who look up to him and feel honoured to show their work alongside his. Also, there are those conversations. The Great Ouse Mud Drawing, 2016, has been a brilliant conversation piece, especially with those people whose opening gambit is: ‘ and did the builders throw their coffee at the wall there?’. That begins a discussion about value, knowledge, skill, seeing the river as never before. Supporting the work of artists who care, whether explicitly or implicitly about the environment is one thing.

There have been some notable one-person shows, which included the first significant exhibition in England devoted to the great natural scientist-artist, herman de vries, On the Stony Path; and also TrashArt, the first in the UK for Jan Eric Visser, a wonderful Dutch artist who recycles all his household paper waste to make sculpture. However, what I have gradually learned, is that the job of the gallery is not about offering solo exhibitions, but to bring artists together across disciplines so as to create a larger reflection about the environmental issues at hand. In fact, even these two exhibitions also involved accompanying displays by other artists – Shaped by Stone was alongside herman de vries. Visser’s show inspired the first community project: Waste Transformed, funded by the British Science Association to involve a group of sufferers of domestic abuse. This turned into a major programme of learning about, and experimenting with waste plastic to make art, which did indeed transform attitudes to science and the environment, as well as giving people personal confidence.

In developing the programme, the environmental theme always becomes the main driver, but that in itself is suggested by the artists’ work. Water Rising formed the main theme for the Spring 2019 exhibition. Some significant artists were involved: Peter Matthews, Susan Hiller, Simon Faithfull, Lynn Dennison; different media from film to painting, including: Annie Turner, (ceramic) Stewart Hearn (glass), Roger Coulam (photography), Sophie Marritt (paint). The initial idea came from the work of Peter Matthews, a regular surfer, who uses the oceans as his studio. spending hours in the water drawing. He then translates the imagery onto canvas, to make paintings, which also act as his overnight shelter on the shore. Literally he lives with his work on many levels. The meditative process, the risk and danger it involves contributes to the power of the result. The lone figure surviving, or being submerged in calm waters, is a recurrent theme for other works in the exhibition. Simon Faithfull’s thought-provoking film, Going Nowhere 1.5, shows a man in a yellow suit purposefully trudging round an ever decreasing circle of sand in an intertidal zone, until he is no longer visible as the camera pans over the vast seas. Though it is intended to be an unspecific location, in fact the work was made off the coastline at Wells Next the Sea in Norfolk, greatly facilitated by the harbourmaster, Robert Smith, who found us the location. Other works are about the more obvious danger and beauty of storms attacking the shore, and then, artefacts in other media tackle practical issues, about efforts to save water as a precious resource, about forming barriers to contain its force. What the exhibition did, was to raise some of our concerns about water in a mixture of ways that art is good at dealing with – imagination, fears, practical solutions, humour, wonder. Thanks to local advice and advocacy, the exhibition attracted sponsorship and involvement of Anglia nWater, which helped us to consolidate its messages and set it on a path of greater impact on wider attitudes to water and its futures.

There are three exhibitions per year. Water will come up regularly, and a river exhibition is planned for 2021. Other themes are recurring, such as nature, plants, and the need for conservation and vigilance; the impact of pollution, climate change. The summer’s theme for 2019 was Fragile Nature featuring two 80 year-old women artists, alongside two in their 20s, demonstrating attitudes to control and freedom in the way they make art. The final exhibition for 2019, On the Edge, tackled crossing categories, hybrids, suburbs – both literal and conceptual edges,. Some of the artists the gallery supports are people I have long known, but an increasing number have come to me to discuss their work, or have been generously recommended by their peers. I am always keen to promote sustainable practice and ideas which inspire wider public involvement. I am also increasingly missionary about the need for an ethical consumer culture around art. If we want good artists to live by their work, we have to buy it, but also we need to make better informed choices in the interests of a healthy environment. With that in mind, we are engaging in a new project looking at environmentally sustainable ethical jewellery. The gallery has always sold jewellery made by artists, and I always maintain that a wearer can use it to talk about the environment, no less than they could from a bigger work of art which is not so portable. The project is being led by Naomi Langford, under the banner GroundJewels, and is funded by the European Regional Development fund, and is about bringing new products to market in innovative ways. As with everything the gallery does, the main aim is to connect art and environment, involving artists and public in working positively together for the healthiest possible environmental future.

What has been very heartening about the whole GroundWork project is how it has been welcomed by the town and by the artistic community both locally and further afield. It has won several awards, among them, one for art and environment from CIWEM, (the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management) and the Centre for Contemporary Art and the Natural World and one from the Mayor of King’s Lynn, for the design of the building’s conversion by Hudson architects and Norfolk Building Co. Most gratifying are the ways in which fruitful interactions through its programming between artistic and environmental themes, between artists and specialists in contingent fields of science and engineering, between writers and film-makers, across different generations and with a widening public at large, have led to the building of a larger culture linking art and environment and with a rippling effect of advocacy and influence. It exemplifies the old mantra of the environment movement, ‘think locally act globally’, or maybe it should be more appropriately ‘think globally, act locally’.

Veronica Sekules, Director

A version of this article was published in Norfolk Coast Guardian, published by the Norfolk Coast Partnership, Spring 2019